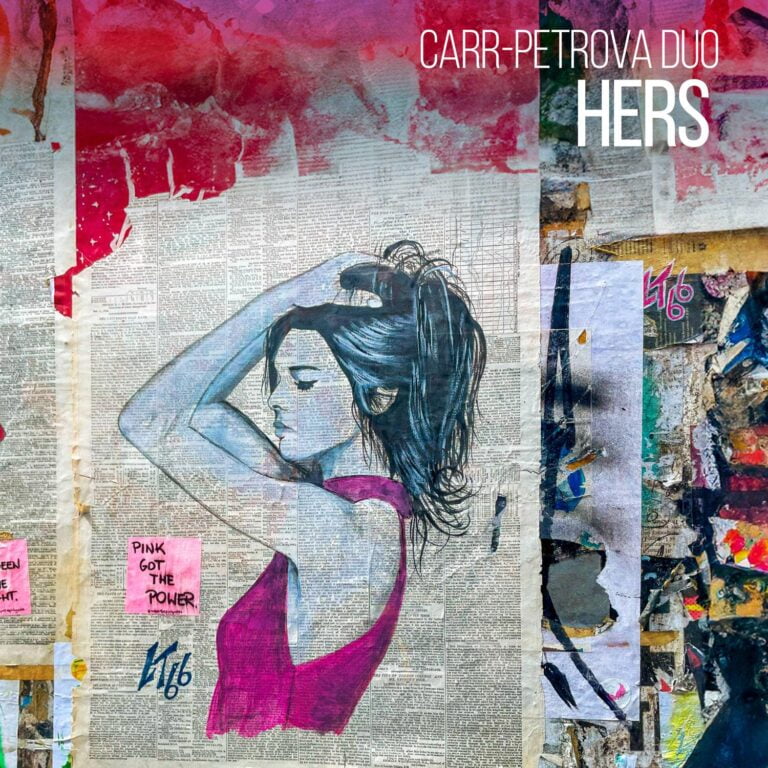

This program celebrates the women who, despite facing discrimination on both personal and institutional levels, nevertheless forged their own artistic paths. From the medieval era to the present, these composers not only often strayed outside of the narrow bounds of society’s expectations, but also produced music that testifies to their creativity, experience, and brilliance. As the performers describe, it captures “the vision, strength, resilience, and vital contributions of women throughout history.”

Born and raised in Little Rock, Arkansas, Florence Price (1887-1953) almost immediately faced obstacles to her musical training; the city’s white instructors refused to work with her, leaving her mother in charge of her artistic development. Throughout her life, she was plagued by such discrimination; in a letter to the conductor Serge Koussevitzky (conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra at the time), she writes explicitly of her “two handicaps…sex and race.” Despite this, she became a nationally acclaimed composer. Her songs were championed by famed contralto Marian Anderson, while her Symphony in E minor was premiered by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra—the first orchestral work by an African American woman to be performed by a major American orchestra. Many of her works languished in manuscript form, forgotten for over half a century. After being rediscovered in a dilapidated home (Price’s former summer house) in 2009, they are happily now gaining appreciation through publication and performance. Elfentanz (“Dance of the Elves”) is one of several short pieces originally written for violin and piano. It opens with a spritely theme made effervescent by pervasive offbeat rhythms, capturing the whimsy of the title. A lushly romantic middle section follows, with soaring melodies and yearning harmonies. The impish music tiptoes back in, however, and the work closes with a playful pizzicato wink.

Clara Schumann (1819-1896) was hailed in her lifetime as a virtuoso performer, described by her masculine contemporaries (including her husband, Robert Schumann, as well as Johannes Brahms and Franz Liszt) as the “priestess” of the piano. She also composed, often featuring her own works on recitals. Despite her well-recognized prowess, Schumann often confessed her self-doubt in her diary about her abilities to both compose and perform. In 1839, for instance, she lamented:

I once believed that I had creative talent, but I have given up this idea; a woman must not wish to compose—there never was one able to do it. Am I intended to be the one? It would be arrogant to believe that.

Despite her hesitations, the year of 1853 nevertheless was a prolific one compositionally. Written in July of that year, the Three Romances for Violin and Piano, op. 22 (transcribed here for viola) were dedicated to the celebrated violinist Joseph Joachim; the pair performed the work several times together, including once for the reigning monarch of Hanover, King George V. From the very opening of the first movement (Andante molto), we hear the dialogue between the instruments. It opens with a series of questions, and a sense of longing—in both melody and harmony—is pervasive. In the Allegretto that follows, Schumann plays with quicksilver changes of mode; the opening theme in G minor, which Schumann directs performers to play with “delicate expression,” is contrasted with a lighthearted section in the parallel major. Listen, too, for such shifts in the final moments of the movement. The indication of the finale—Leidenschaftlich schnell (“passionately quick”)—captures something of its character, as a long, pathos-filled melody unspools smoothly over bubbling piano arpeggios.

Writing of Prayer, composer Vivian Fung (b. 1975) comments on the personal nature of this piece, and speaks to her experience as a mother and composer:

Prayer is, in essence, an aberration, for under no other circumstance in the past (or probably in the future) have I worn my heart on my sleeve as transparently as I have with this piece. In times of crisis and peril, we have but the reliance on faith – from the profound faith in humanity, faith in love, and faith that we will persevere and get through this with dignity, to the mundane faith that I would complete the piece within the extraordinary conditions that faced me, with a young child at home 24/7, a bronchial infection, and a very tight timeline (ultimately, a matter of days) to complete the piece…

In both melody and meaning, the work pays homage to another remarkable woman: Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179). In today’s parlance, we might describe her as a multi-hyphenate: she was an abbess responsible for her Benedictine community, a visionary who recorded and shared her prophetic insights, a prolific writer in genres from medicine to hagiography to poetry, and a composer with an original, distinctive voice. That she – a woman – accomplished all of this in the twelfth century, within the confines of the deeply patriarchal church makes her all the more extraordinary. Prayer takes inspiration from one of Hildegard’s antiphons, O Pastor animarum (“O Shepherd of our souls”). The chant is characteristic of the composer’s style, with monophonic melodies emphasizing the meaning of the poetic text through rhapsodic melismas; liberare, (“to free”), for instance, is stretched out over many notes. Fung adopts (and adapts) the opening, rising contour of Hildegard’s melody, piecing it together slowly over rippling accompaniment, before allowing the viola to triumphantly intone it more fully.

The origin of Romance, by American composer and pianist Amy Beach (1867-1944) is uniquely tied to the celebration of women artists; it was premiered during the Women’s Musical Congress, part of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Performed by Beach herself on piano and Maud Powell on violin, the concert was one of many devoted exclusively to music by women. This recital must have been particularly sweet for Beach, whose performance career was constrained due to her husband’s wishes; citing his professional status, he requested that she limit herself to only annual recitals serving as charitable fundraisers, and she thus turned primarily to composition as her main artistic outlet. To be honored in this way—as a female composer and performer—must have been satisfying indeed. The work was apparently well received, with an encore performance immediately and vociferously requested by the audience. Their enthusiasm is understandable; the graceful melodies of Romance soar from the lowest to the highest ranges of the instruments, with the parts intertwining and supporting each other equally. The late-nineteenth-century, lushly Romantic harmonic vocabulary and effusive dynamics make the work sing with passion throughout, only finding true closure in the final moments as both instruments ascend and disappear into the ether.

Though Beyoncé (b. 1981) likely needs no introduction, it is nevertheless worth reviewing her astounding career as one of the best-selling and decorated artists of the modern era. At the age of eight, she was already performing semi-professionally with the group that would later evolve into Destiny’s Child; by twenty, she was a household name, and released her first solo album soon after. As her star power grew with each album, so too did her confidence in herself and her artistry; more recent work experiments with different musical genres, explores new themes (most prominently, perhaps, Beyoncé’s own feminist outlook), and integrates divergent forms. Halo comes from her third studio album I Am…Sasha Fierce, which (as the title suggests) is divided into two halves. The double album aimed to capture the self-described bipartite nature of the artist’s identity: the “real” Beyoncé versus her performative alter-ego. “Halo” belongs to the former section, with the lyrics describing how—with the right person—she can let her guard down and trust. Musically, the song is vocally demanding, traversing a wide range, and featuring virtuosic ornaments and melismas. This transcription by Henrique Eisenmann (b. 1986) turns “Halo” into an instrumental rhapsody; the composer transforms the original melody with surprising harmonies, fragments and recomposes motives to create something entirely new, and celebrates the technical capabilities of the two instruments while never losing the feeling of Beyoncé’s original power ballad.

Magnitude by Andrea Casarrubios (b. 1988) was commissioned in 2021 by the Carr-Petrova Duo, and emerged from their Novel Voices Refugee Aid Project, during which the pair traveled across the world performing at refugee camps and engaging with residents in workshops. While in Jerusalem, they witnessed a performance by the “Daughters of Jerusalem,” an ensemble of Palestinian women who study at the Edward Said National Conservatory. The director of the conservatory, Suheil Khoury, described how these musicians are challenging the male-dominated tradition of music making, creating new music that is unique to the ensemble in form and style, and bearing witness to the members’ experiences. Magnitude pays homage to their effect and significance as artists; as Casarrubios writes of the work’s inspiration, “I couldn’t help but consider the magnitude—the tremendous impact they will continue to make, and how their courage in music can have such important repercussions in generations to come.” Throughout the work, the instruments seem to explore this type of influence; motivic fragments first imagined by the piano, for instance, blossom in the viola, becoming more expansive melodies. The accompaniment shifts throughout, shifting between gently syncopated chords to a resolute pedal tone to rippling sixteenth notes to grandiose arpeggios, yet the momentum never ceases. These disparate parts—the initial melody as well as various accompanimental figures—come together as the piece climaxes; musical materials are reinterpreted and recombined into something greater than the sum of their parts. After this profusion of sound, tranquility descends as the two instruments echo each other once more, their dialogue fading into the distance.

In program notes for a concert given in 1977, composer Rebecca Clarke (1886-1979) seized the opportunity to vehemently and proudly claim the Sonata for Viola and Piano as her own, writing “I do indeed exist…and…my Viola Sonata is my own unaided work!” While it might seem strange to assure audiences of the originality and authorship of the work (let alone prove the composer’s very existence), the origin story of the sonata explains Clarke’s clarification. The work was composed for a competition in 1919 sponsored by Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, the American patroness of the arts, in which it received second place (coming runner-up to Ernest Bloch’s Suite for Viola and Piano). The judging was conducted anonymously, with the composers’ names revealed only after the winners had been determined. Coolidge, who cast the tie-breaking vote, later recounted to Clarke the surprise of the jury, saying “you should have seen their faces when they saw it was by a woman!” The shock (and ensuing doubt) reverberated; a number of articles claimed that Clarke had not, in fact, written the sonata, that she had been helped by other composers, and even that the name was a pseudonym for her competitor, Bloch. In an interview recorded on the occasion of her ninetieth birthday, Clarke recalled, “I had an extreme feeling of unreality as if I really didn’t exist…getting a clipping to say that there wasn’t such a person as me was a rather strange experience.”

Yet the Sonata is proof not only of Clarke’s existence, but also of her compositional prowess. The first movement, “Impetuoso,” opens with a declamatory fanfare in the viola. Like Clarke herself, the instrument seems to assert its presence, proclaiming its soloistic power in a brief but impassioned cadenza. With the reentrance of the piano, we are cast more deeply into Clarke’s sound world; a fervent, rising melody is accompanied by modal harmonies and undulating dynamics. The tempestuous music abates, leaving a sinuous, chromatic melody in its wake. This more dreamy, mysterious middle section, replete with floating harmonies, is perhaps the most audible reference to Claude Debussy, whom Clarke cited as a major influence in another interview given late in her life. At moments, the opening material reemerges, hinting at its eventual, powerful return. The “Vivace” that follows opens with an exuberant, dance-like theme in the piano, complemented by the muted viola, which offers colorful accompaniment in the form of strummed pizzicato and whistling harmonics. A shimmering section, awash with atmospheric arpeggiation in the piano and a lyrical, supple viola melody, offers contrast. The sonata concludes with an extensive “Adagio” that, epic-like, seems to move from episode to episode seamlessly. A lonely theme begins our journey; oscillating around one central pitch (G), it wanders freely but always returns home. The viola joins, adopting the meandering melody but supported by rich harmonies in the piano. And while occasional ardent profusions burst forth, this theme is woven throughout, reemerging with a variety of accompaniments; in one of its guises (accompanied by buzzing, sul ponticello tremolos), it slowly gains energy, eventually transforming into the heroic melodic themes of the first movement. Old and new musical material are intertwined in this rhapsodic coda, and the work comes to a virtuosic close.

– Anya B. Wilkening